Caring for the Land

The early morning sun broke through the Ottawa skyline as Algonquin elder Peter Decontie lit the fire. The scent of wood smoke and tobacco filled the crisp autumn air, and the crowd of nearly 200 leaned in to hear his prayer. People had traveled from across the country to attend the National Indigenous Guardians Gathering, and after a water ceremony at the river’s edge led by Elder Josée Whiteduck of Kitigan Zibi First Nation, they stood on Victoria Island—in the heart of the capital—to hear elders speak about the resilience of Indigenous People’s connection to the land.

“The land can heal,” said Dave Courchene, Jr. of the Sagkeeng First Nation in Manitoba. “If we honour the natural laws of the earth, the water and the animals, we will be healthy…Guardians are the leaders and pioneers. You have the knowledge and protocols to care for the land.”

The three-day conference confirmed the guardians’ role in caring for the land. The gathering was hosted by the Indigenous Leadership Initiative, in collaboration with Tides Canada and TNC Canada and with the support of The Pew Charitable Trusts, Ducks Unlimited Canada, the International Boreal Conservation Campaign, Canadians For a New Partnership and other partners.

The guardians came from all over—from the shores of the Mackenzie River in the Northwest Territories to the Atlantic Coast of Newfoundland and Labrador. They included young people, grandmothers, grandfathers and community leaders. Some have been part of Indigenous Guardian programs for decades, some joined within the year. All of them share a deep sense of responsibility to the land.

These Guardians serve as “the eyes and ears on the land and water.” They draw on Indigenous knowledge and western science to patrol protected areas, study wildlife, draft land use plans, monitor industrial development, respond to climate change and restore forests, streams and other landscapes. In the process, they help Indigenous communities express their nationhood. They also connect Indigenous youth with elders, the land and their cultures.

A member of the Tla-o-qui-aht Guardians during a panel about new Indigenous Guardian programs.

Our Presence on the Land

During the opening panel of the gathering, Former President of the Haida Nation Miles Richardson explained that determining how to manage the land is a central part of establishing Nation-to-Nation relations. “The Haida Watchmen grew out of the 1970s and 1980s. When we realized our future didn’t depend on Victoria or Ottawa. We had to look to our own traditions…. For 15,000 years, my ancestors had the courage to listen to the forests, winged ones, four legs. I am proud of those teachings.” he said.

Today, the Haida Watchmen patrol the coast, monitoring fisheries and maintaining cultural sites. “It’s about asserting our presence on the land,” said Haida Fisheries Program Manager Brad Setso. “The general public sees us out there in our uniforms. I can’t overstate the value of that. Now Indigenous and non-Indigenous people come to us to report issues. So does the Department of Fisheries and Oceans.” The Watchmen’s careful management of the land and seas has earned wide respect and helped the Haida Nation shape tourism, protected areas and development on their own terms.

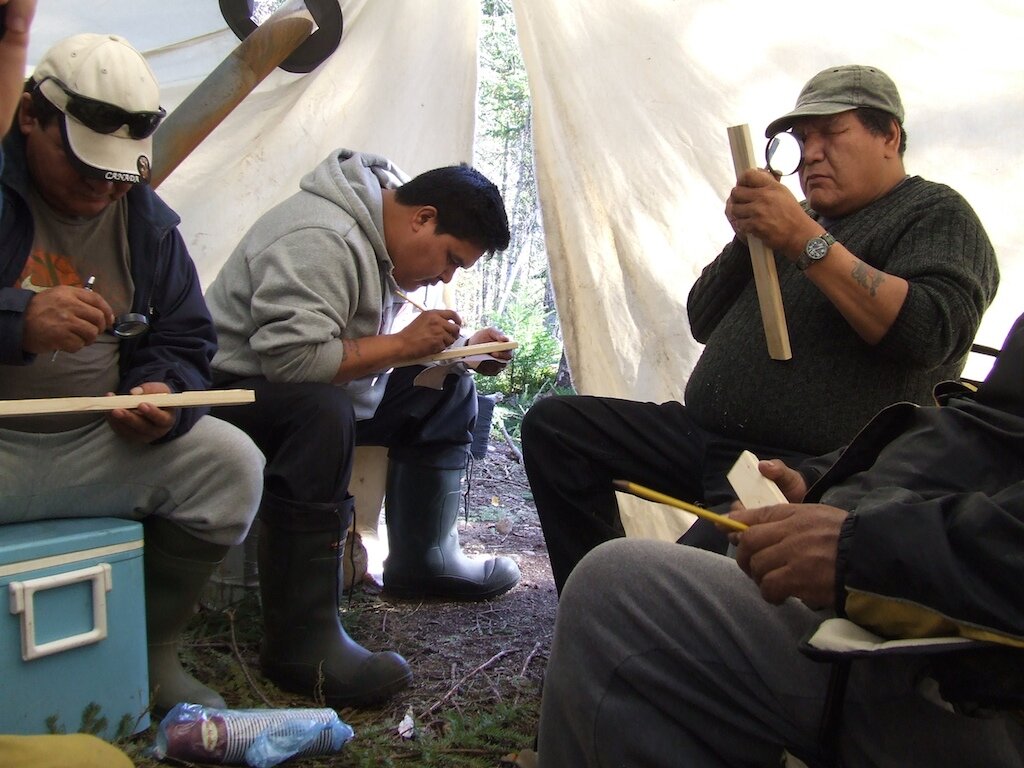

Indigenous Knowledge and Research

Many Guardians underscored the value of Indigenous communities collecting their scientific and traditional knowledge. Guardians often take the lead in gathering this information—asking knowledge keepers about hunting grounds, tracking salmon runs, or evaluating forestry impacts. “Once you’ve done your own research, it changes the dynamic,” said Bruce Maclean, consultant for the Mikisew Cree First Nation. “You sit at the table with your own data and you participate in the conversation.” Communities can draw on that research to drive decision-making.

Throughout the gathering—in panels, Tea and Bannock sessions or casual conversations in the hall—guardians welcomed the chance to learn from one another. Some compared notes about tracking mining activity for the Innu Nation in Labrador and the Taku River Tlingit in British Columbia. Others talked about how they sustain animals that are vital to their regions and cultures—from moose to caribou to salmon. And several talked about the challenge of finding consistent funding amidst the stream of grant proposals.

Innu guardians in Labrador. Grand Chief of the Innu Nation Anastasia Qupee spoke at the Gathering about the guardians work on conservation, forestry and mining.

Youth as Leaders on the Land

The gathering drew guardians of every age, including Captain Gold, the first modern guardian who helped launch the Haida Watchmen in the 1970s. But the presence of so many young people revealed the power of Guardian programs to inspire Indigenous youth. These programs provide meaningful work and professional training tied to traditional culture. “Without the words and direction of elders, I would not be here,” said Gloria Enzoe, the young founder of the Ni Hat’ni Dene program in Lutsel K’e. “I am a root that grew into a tree and I’m branching out and teaching others.”

During one plenary session, Dahti Tsetso of Dehcho First Nations described meeting an Indigenous Ranger from Australia—a country that provides federal funding for programs similar to Indigenous Guardians. The young man said he had dreamed of being a ranger since he was a little boy. “I would like my eight-year-old son to have that same dream,” Tsetso told the crowd. Now she is helping build the Dehcho K’eodhi program to teach young people about caring for the land in the Dene way.

Inspiration and Responsibility

That sense of hope and opportunity permeated the gathering. People were energized by coming together with others whose work expresses their community’s authority and cultural responsibility. They do this work with love for the land and pride in who they are. And they inspire those around them.

At an evening celebration at the Wabano Centre for Aboriginal Health, Mary Simon, the minister of Indigenous and Northern Affairs’ special representative on Arctic issues, honored the work of the Guardians. Scientist and environmental leader David Suzuki called the Guardians “a gift to Canada.” The night ended with youth from Grassy Narrows performing their song, “Home to Me,” singing, “This is a place where we love the land. Let’s work to show our pride.”

The Call for a National Indigenous Guardian Network

The Indigenous Leadership Initiative and its allies are trying to ensure more communities and guardians can express that love for the land. On the final day of the gathering, ILI Senior Advisors Ovide Mercredi, Stephen Kakfwi, Bev Sellars, Miles Richardson and Dave Porter shared a proposal for a federally funded National Indigenous Guardian Network. The network will build on the success of existing Guardian programs and expand over time, adding as many as 200 Guardian programs. It will offer training and provide consistent core funding, helping programs move beyond grant-to-grant uncertainty.

The guardians are “more than a job,” explained Mercredi, former National Chief for the Assembly of First Nations. “The guardians is a movement that will restore our human dignity, a movement where our people will emerge as leaders for the future. A movement based on tolerance and understanding, on honesty and respect. A movement that will allow the elders to sleep peacefully. A movement where even the salmon will be happy and the moose will recover.”